The recent discovery of a 'used' 6d stamp of Ceylon (SG 23) in an old time collection has renewed the controversy which, 140 years ago, led to sweeping changes in the production of British colonial stamps.

In 1858 Penrose Julyan was appointed Agent-General for the Crown Colonies. One of his duties was to supervise the contracts for the printing of colonial stamps which, at that time, were entirely in the hands of Perkins Bacon who had printed all the British stamps from the Penny Black of 1840 onwards but whose monopoly had been dented in 1853 when the Board of Inland Revenue awarded a contract to the rival firm of De La Rue to print fiscal stamps, and then the postage stamps of 3d and above.

Perkins Bacon prided themselves in the fact that their recess or intaglio process was impossible to counterfeit. De La Rue's much cheaper relief process relied instead on fugitive inks which ran or changed colour if any attempt was made to remove the cencellation.

From the outset, Penrose Julyan and Perkins Bacon got off on the wrong foot. The early stamps were issued imperforate and had to be cut apart with scissors. This did not present a problem, despite the fact that the sheets, which had to be dampened before recess-printing, then shrank unevenly when they dried. When machine perforation was adopted, however, it proved virtually impossible to cope with these sheets without the perforations cutting into the stamps. Perkins Bacon solved the problem by using a hand roller with a pin perforation, but the results were very unsatisfactory. Julyan's patience was stretched to the limit when the printers failed to meet deadlines.

More importantly, Julyan examined the contracts and felt that Perkins Bacon were overcharging for an inferior product. He determined to transfer the work to De La Rue who had been given contracts to print halfpenny stamps for Ceylon and fiscal stamps for Jamaica the previous year. From 1860 more and more work was given to De La Rue, but the existing Perkins Bacon contracts still had several years to run before the bulk of the colonial stamp production could be wrested away from them.

Then, out of the blue, Julyan got the opportunity to revoke the Perkins Bacon contracts. He discovered, quite by chance, that the printers had supplied six copies of every colonial stamp to Sir Rowland Hill for the private use of himself and members of his family.

As a result of this unauthorised, if not illegal, operation, Julyan immediately cancelled the contract and ordered Perkins Bacon to surrender the dies and printing plates which were used by their rivals from early 1862 onwards.

It transpired that, some time in the previous year, Perkins Bacon had received a request from Ormond Hill, nephew of the Post Office Secretary, for six sets of stamps. Perkins Bacon, who dealt regularly with Ormond Hill in his capacity as a senior official at the Board of Inland Revenue supervising the British stamps, thought nothing of this request and duly handed over the batches of stamps, amounting to about 450 different in all.

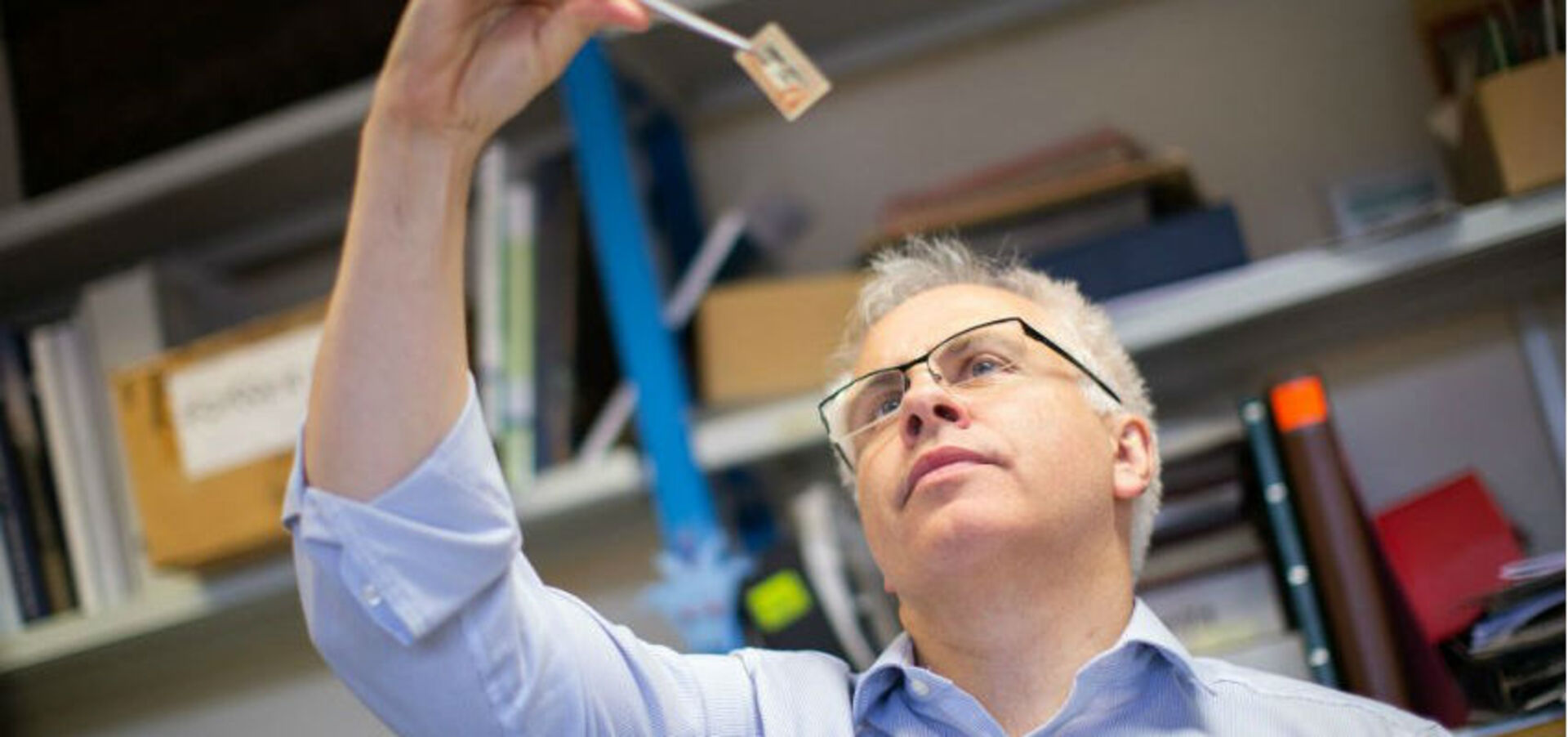

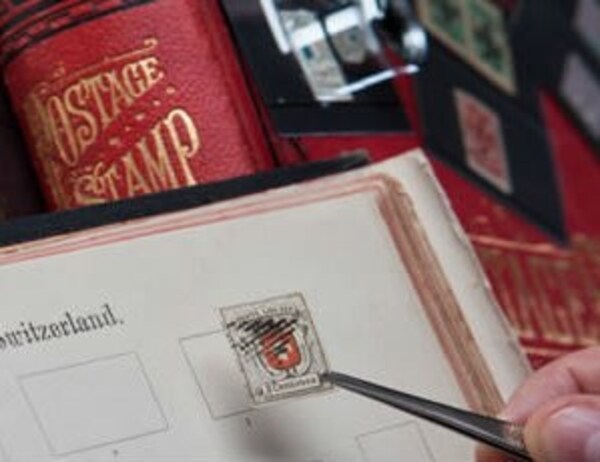

They took the precaution of obliterating the stamps to prevent fraudulent use. For this purpose they employed a barred oval handstamp with the word CANCELLED across the centre and thus unwittingly they created a very rare form of Specimen. These blocks of six were broken up at the time and dispersed among the members of the Hill family. Eventually examples of them percolated through to the philatelic market where they were eagerly snapped up by King George V. As a result, the Royal Philatelic Collection at Buckingham Palace has the most comprehensive group of these rarities.

Another collector who was quick to appreciate their rarity and interest was Robson Lowe and it is interesting to note that his Encyclopaedia of British Empire Postage Stamps, published in the 1950s, priced examples at £10-£40! Today, very few of the Cancelled stamps are believed to be still in private hands and examples fetch thousands of pounds on their fleeting appearance in the saleroom.

General

General

General

General

General

General